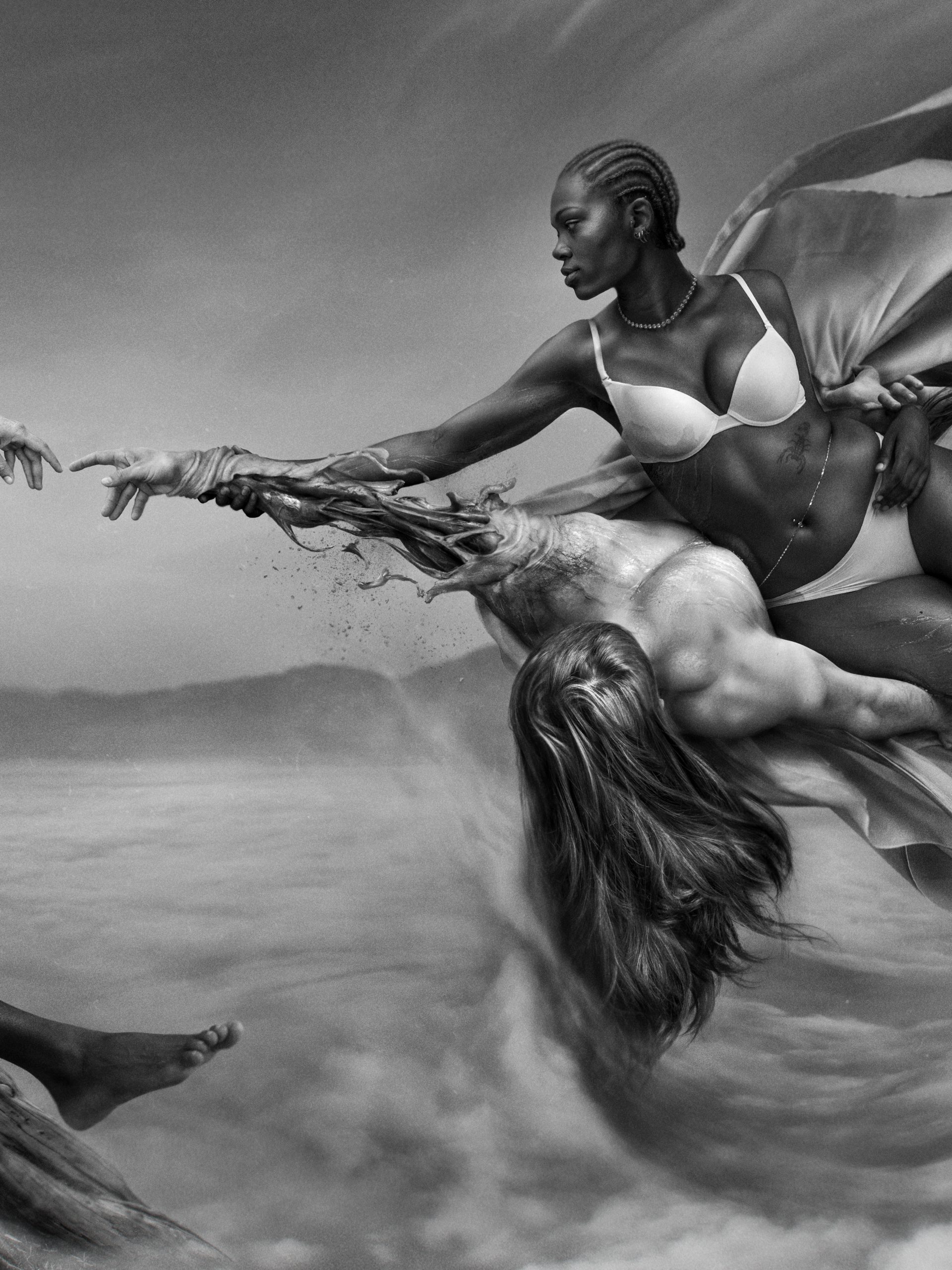

Avec Joyce Richardson & Lonny Rodne @just_lonny_

© Damien Jélaine

Artist Statement

After us, by “us” I mean you and I, still alive, still thinking, still capable of criticism, after us, the arts will no longer be bombs. They will no longer move the masses with cannon shots but, above all, they will no longer raise an eyebrow among the opposing forces.

It has become a true race against the harmless. Black Art is in a perpetual race against harmlessness, against the comfort of others, against their corruptible complicity, against its own punitive exploration, against its commissioned plaintive reflexes.

In my photograph, An Anticolonial Minute: The Disposal of the False Gods, I challenge the notion of art as a weapon of relative, total, or partial destruction, and seek to redefine its role in our contemporary world. I explore the potent capabilities of photojournalism to confront the comfortable silence and complacency of the privileged, aiming to dismantle the stronghold of colonialism’s false gods.

References

Through my artistic journey, I have been profoundly moved by the works of renowned photojournalists. It’s James Nachtwey in Eastern Europe and grief-stricken mothers mourning their lost sons as their remains are dug up from a mass grave. It’s Sebastiao Salgado in Sudan, where famine is used as a weapon of massive destruction in warfare. It’s McCullin in the Congo, capturing white mercenaries on an open-air safari for black lives. It’s the flames of imperialist hell erupting from the earth of Kuwait in 1991. It’s the deep scars inflicted by human nature on human nature, tirelessly.

And amidst all of this, these photographers armed themselves with beauty. The ultimate tool in order for fragile Western masses, dulled by comfort, to catch a glimpse of the shared horror of the other world. And since I could never find myself in a conflict zone where my appearance would only serve to get me killed, one way or another, the pursuit of this powerful and tragic “Beauty,” raw and realistic to the core, became an obsession. I would use it to photograph a war unseen, but whose impact is just as corrosive and deadly. My war. The war of the neocolonized.

My obsession with photographic archives led me to the works of Alice Seeley Harris, a British missionary and photographer whose images of the Congolese genocide by the Belgians are now a visual reference for the atrocities of King Leopold II’s reign. The era of the black stumps. So many stumps, thousands of African joints cauterized, captured around black faces from which even the pretense of pain seemed to be banned. The black necrosis became excessively easy to look at, observe without flinching, and accept without questioning beyond its barbaric and inherently racist nature. I wondered where this sudden desensitization to mass death came from. And why did it only occur when faced with corpses or mutilated bodies resembling mine? My favorite photographers were to blame, inadvertently so. The rise of 20th-century press magazines compelled them to send their image-making emissaries to the most violent and bloody conflict zones in modern history. The Congo in the second half of the century, South African apartheid, the Sudanese civil war, the Rwandan genocide, and more.

The returned photographs, each one more aesthetically tragic than the last, inadvertently taught the Western eye the grammar of black putrefaction. The norm of the emaciated African child with a distended belly was born. Not seen as a context of war but perceived as extreme poverty. The standard of flesh slashed by machetes emerged without the context of political demoralization. Black individuals covered in flies, dead or alive, became nothing more than an extension of the African landscape and dialogue, reduced to mere tragic scenery.

Seeley Harris ultimately shot what would become her most famous photograph: that of a father named Nsala observing the severed hand and foot of his daughter Boali. A photo I’ve seen and revisited countless times until its composition started to question me. Why did this composition suddenly feel so familiar? Like the most macabre déjà vu. A father, in profile, with other figures in the background observing the scene, with the hand of his child at the center. Fucking Michelangelo. The “Creation of Adam,” the « Trinity Project of the art world », the most effective existential bomb and civilizational weapon of all time. Everything was there, except the power. Everything was there, except creation, replaced by destruction. If God was creating his son, Nsala was losing his daughter. If God was pointing a finger, Nsala was retracting his hand. From a total colonial icon arose total colonial damage, and that was the starting point of my work.

Technique

Exclusively employing my journalistic-style photographs, meticulously depicting anatomically realistic bodies in stark black and white, I dedicated two relentless years to crafting An Anticolonial Minute: The Disposal of the False Gods. This opus emerged not as a mere reinterpretation of Michelangelo’s masterpiece, but as an unyielding and visceral vendetta, confronting the sinister origins and historical repercussions inflicted upon Caribbean communities.

For this piece, I delve into two distinct techniques that have become integral to my creative process.

The first one, which I called “Photopiecing,” involves shooting a vast array of visual elements and building a personal image repository. I photograph characteristic clouds from the Antilles, mountains from the island of Désirade, decapitated trees from the forests of Guadeloupe, residues and food waste of animal origin, endemic vegetation, diverse veils, and fabrics, as well as models representing different racial backgrounds, encompassing both racially diverse individuals and white models. Additionally, I include liquids of varying consistencies in this collection. In the end, over ten thousand photographs were meticulously captured to serve as raw material for this large piece.

The second technique, “Photobending,” demands meticulous cutting and folding of the photographs using Photoshop, carefully preparing them for compositing. Through the cutting process, I extract specific elements from each image, while the folding allows me to arrange and overlap them creatively, resulting in accurate anatomical realism.

Research

The anatomical research traced a tortuous path within my artistic mind. I embarked on exploring the bodies of the Renaissance, often dissected and studied during public autopsies, and juxtaposed them with the contemporary censorship of bruised and mutilated bodies of our time, on the Internet. Initially, this quest sparked a sort of fascination, an eerie allure for the macabre beauty and enigmatic details of the human machinery. But gradually, the exploration turned into an arduous journey, unearthing the darkest aspects of our species.

Each day, I found myself submerged in an ocean of indescribable pixels, bearing witness to the horrors that plague our world. The wars of South American cartels, the scars of countless ongoing civil conflicts as I write these words, all of these abominations beyond comprehension. The hellish of these conflict images shook me to my core. I quickly understood that this experience would leave indelible scars on my soul.

As I sought to replicate the gritty realism of war photographers’ experiences, I found myself amidst unspeakable pixels, knowing that I could never fully recover from that exposure. Yet, the more I tainted my soul, the more my mind became a filter: horror and death should only transpire through a form of unyielding beauty in the final artwork, or else I’d become a monstrous voyeur among many.

A Fair Mirror

Although my depictions of Adam, Eve, and the Simulacrum of God emerged as colonial adversaries, devouring my world and that of my kin for centuries,

continuing to write and rewrite the destinies of peoples, imposing their will with relentless ferocity… they remained my creations in this piece. To understand them, to treat them justly, and to extend their grace beyond their necessary and legitimate destruction, embracing their undeniable physical beauty, their profound gazes, and European grace was imperative. It is through their very existence that I collide with my own demons, my ambivalent status as a Western artist confronted with the truth. This artistic quest had transformed into an intimate challenge: to destroy without soiling. To transform these colonial entities into remnants of a powerful Europe, of a civilization both fascinating and cruel.

In this pursuit to reveal the essence of the tragic historical relationship between me and my enemies, to transmute pain into beauty, I explore the limits of my own gaze. I become the mirror and the medium, oscillating between annihilation and creation. A complex duality that compels me to question the artist’s responsibility in the face of the world’s horrors, to plumb the depths of my own conscience.

Thus, the essence of my photograph lies in this tension, in the search for a delicate balance between captivating beauty and unspeakable brutality. It is within this space between two worlds, between their shadows and our light, between our shadows and their light, that I endeavor to forge a unique artistic language, ruthless and tender simultaneously. A photography that, I hope, will offer the spectator a disconcerting immersion into the history, complexity, and the birth of rage as consequences of colonization, while provoking contemplation on my role in our troubled world.